5 Conceptual design or modeling: the Pond Trade model

5.1 Starting with models as references

To complement the initial “brainstorming” of conceptual models, modellers will often search and review models already published on related subjects, considering if these could be reused, at least as an inspiration.

Keeping yourself posted about the ABM community may give you an edge. Unfortunately, academic publishing has become a saturated media, and it is relatively hard to be updated about specific types of research, such as ABM models, which are often spread in many kinds of publications. Public model repositories, such as CoMSES and initiatives like the modular library from NASSA may aid you greatly in this task. But, ultimately, finding a relevant model will depend on your skills in Internet search (including prompting the right LLM!) and the attention others have put to preparing and publishing their models.

In the following example, instead of building a model from scratch, we will be visiting the conceptual model corresponding to the Pond Trade model, designed by me in 2018 to facilitate learning ABM, mainly for archaeology and history.

Having started with a mechanism definition (the model), which already is declared to represent a phenomenon relevant to archaeologists (trade), we will then proceed to select a set of types of evidence and a case study to demonstrate it.

5.2 The Pond Trade context

The Pond Trade model represents mechanisms that link cultural integration and economic cycles caused by the exchange of materials (“trade”) between settlements placed in a heterogeneous space (“pond”). The Pond Trade design intentionally includes several aspects commonly used by other ABM models in archaeology and social sciences, such as multiple types of agents, the representation of a so-called “cultural vector”, procedural generation of data, network dynamics, and the reuse of published submodels and algorithms.

The Pond Trade model and all its versions were developed by myself, Andreas Angourakis, and are available for download in this repository and its original repository.

A similar model, TravellerSim, was presented by Graham and Steiner (2008), who were revisiting an older non-ABM model (Rihll and Wilson 1991, 59–95), even though one was not based on the other. All three, and indeed many more, coincide in the “informal formulation” of the core mechanism, rooted in economic theory, relating the size of settlements to how they are interconnected.

Such a situation, where similar mechanisms are modelled from scratch several times by different researchers, is, in fact, prevalent in the ABM community. There is a growing number of publications and models spreading over many specialised circles, which do not always cover all details about model implementation. Meanwhile, there is still no adequate logistical support for orderly sharing and searching for models across disciplines, despite the efforts made by CoMSES. The primary mission of NASSA is to offer a long-term solution to this problem.

5.3 Phenomenon

The Pond Trade model core idea is inspired by the premise that the settlement economy’s size depends on the volume of materials exchanged between settlements for economic reasons (i.e. ‘trade’). The “economic” size of settlements is an overall measure of, for example, population size, the volume of material production, built-up surface, etc. The guiding suggestion was that economy size displays a chaotic behaviour as described in chaos theory: describing apparently “random” oscillations as an emergent of deterministic mechanisms. The cause of this chaotic behaviour would be presumably the shifting nature of trade routes as the outcome of many context-dependent decision-making processes. Furthermore, in addition to variation in time, routes would be bounded to more stable constraints in space, explicitly concerning the contrast of land in front of maritime and fluvial routes.

5.4 Mechanism: a first approach

The initial inspiration for a model design may be theoretically profound, empirically based, or well-connected to discussions in the academic literature. However, the primary core mechanism of a model must narrow down to a straightforward, intelligible process. In this case, the focus is to represent a positive feedback loop between settlement size and the trade volumes coming in and out, which can be described as follows:

Core mechanism:

- Traders choose their destination trying to maximize the value of their cargo by considering settlement size and distance from their base settlement;

- An active trade route will increase the economic size of settlements at both ends

- An increase in size will increase trade by: - Making a settlement more attractive to traders from other settlements

- Allowing the settlement to host more traders. - An active trade route will increase the cultural similarity between two settlements through the movement of traders and goods from one settlement to the other (cultural transmission)

Elements (potentially entities):

- settlements

- traders

- terrain

- routes

- goods

Preliminary rules:

- Coastal settlements of variable size around a rounded water body (“pond”)

- Traders travel between the settlements

- Traders travel faster or slower depending on the terrain - Once in their base settlement, traders evaluate all possible trips and choose the one with the greater cost-benefit ratio

- Traders carry economic value and cultural traits between the base and destination settlements - Settlement size depends on the economic value received from trading - The economic value produced in a settlement depends on its size - The number of traders per settlement depends on its size

Targeted dynamics:

Settlements that become trade hubs will increase in size and have a greater cultural influence over their trade partners, though also receiving much of their aggregated influences

The display above might seem somewhat chaotic and vague, but it intends to represent one of the best-case scenarios in terms of the conciseness of the initial conceptual model. There are no golden rules, good-for-all schemes or “right words” at this stage. You should start from your (or your team’s) knowledge and hypotheses and move these into implementation, where you may revise them. In my opinion, you should not limit your ideas beforehand to external frameworks (e.g., some of the points required in the ODD).

Still, we count here on the second layer of the conceptual model, which allows us to have an overall plan of the implementation steps.

5.5 Base terrain

The Pond Trade model requires a “geography” of discrete spatial units. For simplicity, we define two types of spatial units, land and water. The general configuration should form a main water body, the “pond”, surrounded by land, and settlements should be placed around this water body. This gives us the context for having a differential cost in travelling between settlements (assuming that travel over water is easier/faster), and allows us to work with the concept of route in an heterogeneous terrain.

5.6 First-tier dynamics

To pace the complexity of modelling process, we organise the further development of the Pond Trade conceptual model in two tiers. The first tier will aim to cover only some aspects of our initial formulation:

Mechanisms: - ↑ global level of productivity → ↑ settlement production

- ↑ number of settlements → ↓ distance between settlements - ↑ settlement size → ↑ settlement production → ↑ trade flow from/to settlement → ↑ settlement size

- ↑ settlement size → ↑ number of traders based in settlement → ↑ trade flow from/to settlement → ↑ settlement size

- ↑ trade attractiveness of route A to B → ↑ trade flow A to B

- ↑ distance A to B → ↓ trade attractiveness A to B - ↑ size B → ↑trade attractiveness A to B - ↑ trade flow A to B → ↑ trade flow B to A

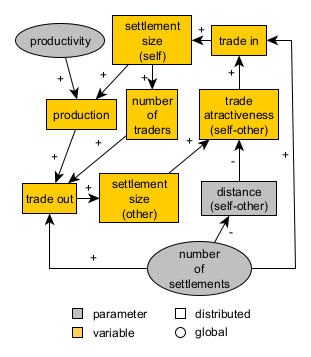

Pond Trade conceptual model at start (first tier)

Track the paths made by the arrows in our diagram. Notice that we have drawn a system with at least two positive feedback loops (cycles with “+” arrows), one mediated by the production and the other by the number of traders.

Expected dynamics: differentiation of settlements (size) according to their relative position

5.7 Second-tier dynamics

To reach the full version of the Pond Trade model, we also need to address the aspects related to cultural transmission and evolution:

Mechanisms:

- ↑ global undirected variation in culture → ↑ or ↓ cultural similarity A and B (cultural drift)

- ↑ trade flow A to B → ↑ cultural similarity A and B (cultural integration)

- ↑ global cultural permeability → ↑ cultural similarity A and B, if A and B are trading (acceleration of cultural integration)

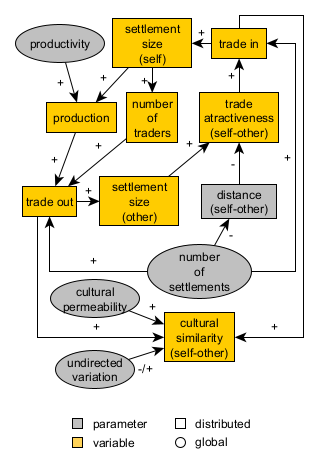

Pond Trade conceptual model at start (second tier)

Expected dynamics: cultural integration as the outcome of exchange network dynamics

5.8 Evidence and case study

Having a generic conceptual model that covers the definition of a phenomenon and mechanism, we proceed to select a case study that offers both a real-world context and archaeological data to which we can adapt the Pond Trade model.

Paliou, Eleftheria, and Andrew Bevan. 2016. ‘Evolving Settlement Patterns, Spatial Interaction and the Socio-Political Organisation of Late Prepalatial South-Central Crete’. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 42 (June): 184–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2016.04.006.

Summary (by Google NotebookLM)

This research article investigates socio-political organization in south-central Crete during the late Prepalatial period (ca. 2300–1850 BC), a period before the well-documented Minoan palaces. Employing spatial interaction models and regression-based predictive modeling, the authors analyze settlement patterns and artefact distributions (specifically Minoan seals) to identify potential local power centers. The study addresses the challenges of incomplete archaeological data by incorporating simulated settlement locations, improving the accuracy of the analysis. The findings suggest the existence of three to four local power centers, rather than a single dominant center, during the late Prepalatial period, with a shift towards a single dominant center at Phaistos in the subsequent Protopalatial period. The study highlights the combined use of computational modeling and material culture evidence to understand past socio-political dynamics.

Takeaways for our conceptual model

- Case study: settlement interaction and the emergence of hierarchical settlement structures in Prepalatial south-central Crete

- Phenomena to represent: cycles of growth and collapse (i.e., fluctuations in the scale of site occupation). Focus on site interconnectivity and its relationship with settlement size.

- Main assumption: topography, transport technology, exchange network, settlement size, wealth, and cultural diversity are intertwined in a positive feedback loop (i.e. big gets bigger or busy gets busier).

- Dynamics we expect and want to explore: the long-term consolidation of central sites and larger territorial polities.

Since Paliou and Bevan (2016) also tackles research questions on settlement patterns and interactions, the study offers us an opportunity to compare ABM with other approaches, such as the gravity spatial interaction models referenced in the original study. Hopefully, you will gain an intuitive perception of the advantages and caveats of ABM in front of more analytical or data-driven approaches.

With site distributions and artefactual classifications, archaeology offers an opportunity for us to estimate aspects such as population density and economic and cultural interactions. However, to relate the socio-ecological past to the material evidence in the present, we must inevitably use an explanatory model. There are many published models relevant to this topic, several already mentioned by Paliou and Bevan (2016). However, few are formalised to some extent, and fewer are available as reusable implementations. Luckily, some of these are ABM models (see ABM in archaeology and References).

Our objective adapting the Pond Trade model to this case study is to delve deeper into the expectations of our current knowledge about the growth of settlements and the formation of local polities in this crucial period, preluding the Minoan palatial institution. As in the original paper, we will need to assume a series of conditions and behaviour rules, considered valid for this context, given historical and anthropological parallels. However, in an agent-based model, such assumptions can be made more explicit as part of the model and, thus, testable as an explanation.

As mentioned, ABM is particularly hungry for specifications, many of which are not even dreamed of by the average archaeologist. In this tutorial, we will try to maintain an intermediate level of model abstraction, avoiding many details that would normally be included in the ABM-SES approach in archaeology.

5.9 Expanding the Pond Trade model

However, in addition to the core mechanism, we must consider another aspect to better approach our case study.

The Pond Trade model has several caveats. Like any other model, it is incomplete and greatly simplifies those aspects of reality that we chose not to prioritise. One of the most significant simplifications is that each settlement’s production is only dependent on a general term of productivity, independent of the land accessible to its inhabitants.

This limitation is not a significant problem if we are dealing with a straightforward terrain, like in the original Pond Trade where we only differentiate between land and water. However, we eventually aim to apply the model to a specific region and use the available geographical and archaeological data. Therefore, we lay out a potential expansion of the original Pond Trade, which will enable us to factor in the diversity regarding the land productivity around settlements.

Mechanisms:

- ↑ settlement size → ↑ settlement territory

- ↑ settlement territory → ↑ production (of land)

- ↑ productivity (of land) → production (of land)

- ↑ production (of land) → ↑ production (of settlement)

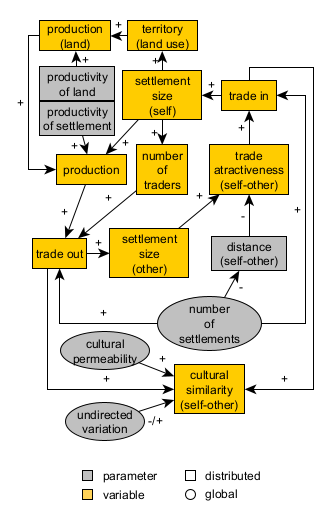

Expanded Pond Trade conceptual model at start

Notice that, with this expansion, we are again introducing a positive feedback loop or splitting the one that already involves production. This time, however, instead of relying on a global parameter, we are regulating the process through a location-specific value (i.e., productivity of land).

Expected dynamics: production is ‘grounded’, i.e., dependent on each settlement catchment area size and productivity

5.10 Conclusion

Once a minimum conceptual model is defined, we should use caution when attempting our first implementation. A relatively simple model may still correspond to code that can be very difficult to control and understand. Simulation models are very sensitive to the presence of feedback loops. You will notice later in the step-wise implementation of the Pond Trade model, that the positive feedback loops present in the conceptual model are not included until the most basic and predictable aspects are properly defined and their isolated behaviours verified.