4 How to do ABM

In the remaining sections of the Introduction, we will go deeper in describing the workflow of ABM. First, we lay out this workflow as it is commonly declared by practitioners, as a sequence of well-ordered steps that may be iterated in a revision cycle. Then, we introduce a few elements ‘behind the scene’ that stretch the ‘steps’ metaphor to its limits. We then review a few practical recommendations that, hopefully, will aid future ABM modellers. These include the verification-refactoring cycle in programming, the use of modular code, and the importance of remaining explorative while designing a model.

4.1 Modelling “steps”

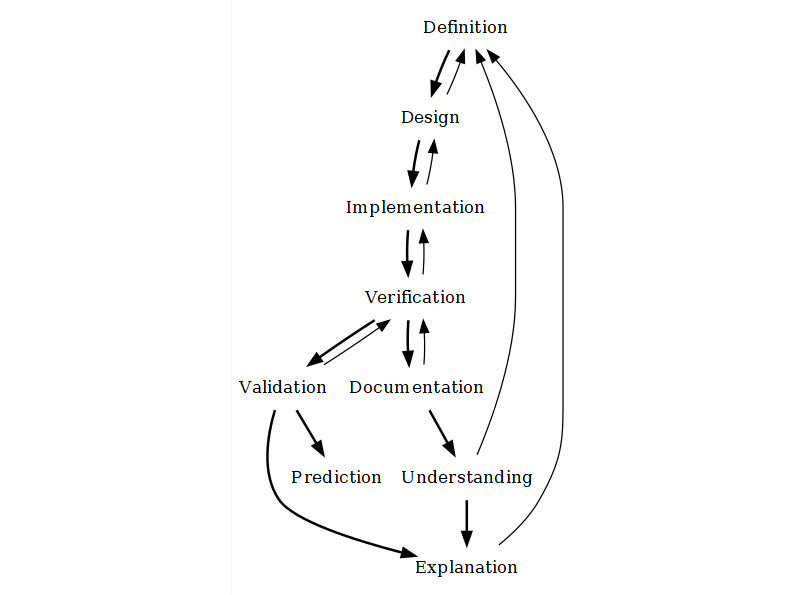

Modelling with ABM can be divided into steps, most of which are identified by the community of practitioners as either normative or recommended phases of model development. With minor variations, these are also recognised in other simulation and non-simulation modelling approaches.

The steps are:

Definition of the research question and phenomenon. To define a research question and the phenomena involved, we must think in terms of systems, identifying and defining a set of elements we deem relevant and their interrelationships. In this initial step, the key is to delimitate the target system, within which external, undefined factors do not overly determine the interaction of elements. Here, we must decide on what is relevant for us and set aside the rest. Ideally, we should move to the next step only once we have a hypothetical mechanism to focus on, formulated roughly but in detail enough so we can formalise it later. We will call this our conceptual model.

Design or conceptualisation. Designing a model is essentially to find a formal definition able to represent the phenomena, as we have defined in the previous step. In this step, we go from a vague text description of the natural system we observe and its expected dynamics to a mathematical or algorithmic representation of the artificial system we want to build. At this stage, it is critical to define our model’s main variables, including any inputs and outputs. The latter will be particularly important to how simulation results can be compared to empirical data to validate the model. During model design, our conceptual model is formalised progressively, ideally up to the point where implementation is made immediate.

Implementation. To implement the model is to effectively write down our model design as a piece of software (i.e., through programming). While other mathematical models could remain unimplemented, ABM models are hardly useful if not able to be solved through computer simulation. However, a model implementation carries much extra baggage, and many possible implementations exist for the same model. Therefore, modellers and their audience must differentiate between the model and its implementation.

Verification. To verify a model implementation, we run a series of tests on the model code and compare the results with our expectations as model designers. If we wrote a fragment of code to calculate “2 + 2” expecting “4”, we should get “4” after running it. On the other hand, verifying a model (not its implementation) can only be done by running an implementation, which we assume is correctly representing the model. If our model states that “2 + 2 = 4”, and our implementation returns “4”, then we would conclude that the logic behind our model is correct.

Validation. To validate a model is to iteratively match the conditions of our model (assumptions, parameter values, etc.) to measurable conditions in the targeted system and the results of simulations to equivalent variables measured in the targeted system. ABM modellers often regard validation as an extra, lengthy process, usually separable from the tasks involved in defining, implementing, and exploring a model. Validation is never an absolute term: it will depend on the amount of data available and the specific criteria chosen. A validated model is not a “correct” model, nor a model failing validation is a “useless” model.

Prediction. A model that is robust in validation might be further considered as reliable to predict new evidence. In fact, validation is often made through approaches that emulate prediction by reserving a set or type of data to be compared with the model output.

Furthermore, a few authors, myself included, also like to highlight two additional steps that are generally not acknowledged:

Understanding. The modeller must understand the model, know the variety of dynamics it can generate, and be aware of its limitations regarding the representation of the target system.

Communicating or Documenting. The understanding obtained by the modeller at one point is of little use to others and, eventually, her or himself in the long-term future. To ensure that such an understanding is passed through, we must invest significant time in documenting the model’s conceptual design and source code. Note that this is not equivalent to an academic publication, especially because most scientific journals push for a greater emphasis on the results rather than the bits and pieces of simulation models.

4.2 Modelling “(mis)steps”

However, building an ABM model is, in practice, a process that is significantly more complicated than the steps listed above. There are many shortcuts, such as finding a model or piece of code that can save months of work, but, more often, there are obstacles that test ABM modellers and the teams of researchers working with them. Some modellers (myself included) have characterized this as a ‘reiterative’ process, often drawing diagrams showing these steps in well-planned cycles. However, it might be more exact to lose the walking metaphor altogether.

The first problematic situation that comes to mind is, of course, the “technical issues”. Developing ABM models requires a set of skills that are rare and hard to obtain and maintain meanwhile doing other research tasks. Probably the most prominent skill of a modeller is programming, which involves conceptual abstraction and certain agility with the software being used. The latter is made even more relevant when the software used is poorly documented or requires a particular set up upon installation. This is undoubtedly the first entry toll of the ABM community for researchers in the humanities and social sciences. Still, the hardships on this side usually are surpassable with continuous training, support from more experienced modellers, and choosing the right software. Still, it is undeniably a long-term commitment.

Unfortunately, issues related to ABM go deeper than code and software. For example, during the model design process, researchers might need to ask inconvenient and trivial questions about the phenomena represented, which raise a surprising amount of controversy and doubt and can even challenge some of the core assumptions behind a study. In archaeology, this may come as aspects that are considered out of the scope of empirical research due to the limiting nature of archaeological data compared to disciplines that focus on contemporary observations (e.g., anthropology, sociology, geography). Should an archaeological ABM model include mechanisms that cannot be validated by archaeological data (at least not in the same sense as experimental sciences)? This is probably the most important unresolved question in this field and possibly the one most responsible for hindering the use of ABM in archaeology.

These complications can be considered problems and opportunities, depending on if and how they are eventually resolved. In some cases, the difficulty will present a new idea or approach. In contrast, in other cases, dealing with it might cost valuable time and delay the research outcomes beyond any external deadlines (e.g., project funding, dissertation submission). The exercises in this course are presented in the spirit of safeguarding modellers in training from being stopped short by some obstacles while pursuing their research agendas using ABM.

4.3 Best practices

Before jumping into practice, let us go over three general strategies that can offer a way out to at least some of the problems mentioned here. These strategies are: version control, refactoring regularly, enforcing modularity and being explorative.

4.3.1 Version control

Since modelling an ABM model eventually involves creating a piece of software (implementation), it is important to use version control to keep track of changes and to be able to revert to previous versions if necessary. This is especially important when working in a team, but also when working alone. Version control is also useful for keeping track of changes in the documentation and for keeping track of changes in the data used for the model. This kind of technology is an essential part of the software development process and we will dedicate a whole day to it, later in the course.

4.3.2 Refactoring regularly

By definition, refactoring means that your code change but remains capable of producing the same result. Refactoring encompasses all tasks aiming to generalize the code, make it extendible, and also make it cleaner (more readable) and faster.

However, there is a trade-off between these three goals. For example, replacing default values with calculations or indirect values will probably increase processing time. In practice, this trade-off is irrelevant until your model is very complex, populated (many entities), or must be simulated for many different conditions. I recommend always being attentive to the readability, commentary, and documentation of your code. Assuming you are interested in creating models for academic discussion (i.e., science rather than engineering), the priority is to communicate your models to others.

There are many actions in code that can be considered refactoring. Too many for us to enumerate here. Probably the best and more educational approach is to encounter examples of practices, both good and bad, think about them, and try to do better. In this sense, we will go over several examples along with the tutorial that hopefully will illustrate when and how you should refactor your model code.

4.3.3 Enforcing modularity

One of the most critical aspects related to refactoring is code modularity. The so-called Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) has been established in software engineering and serves as an excellent guiding principle for building complex code.

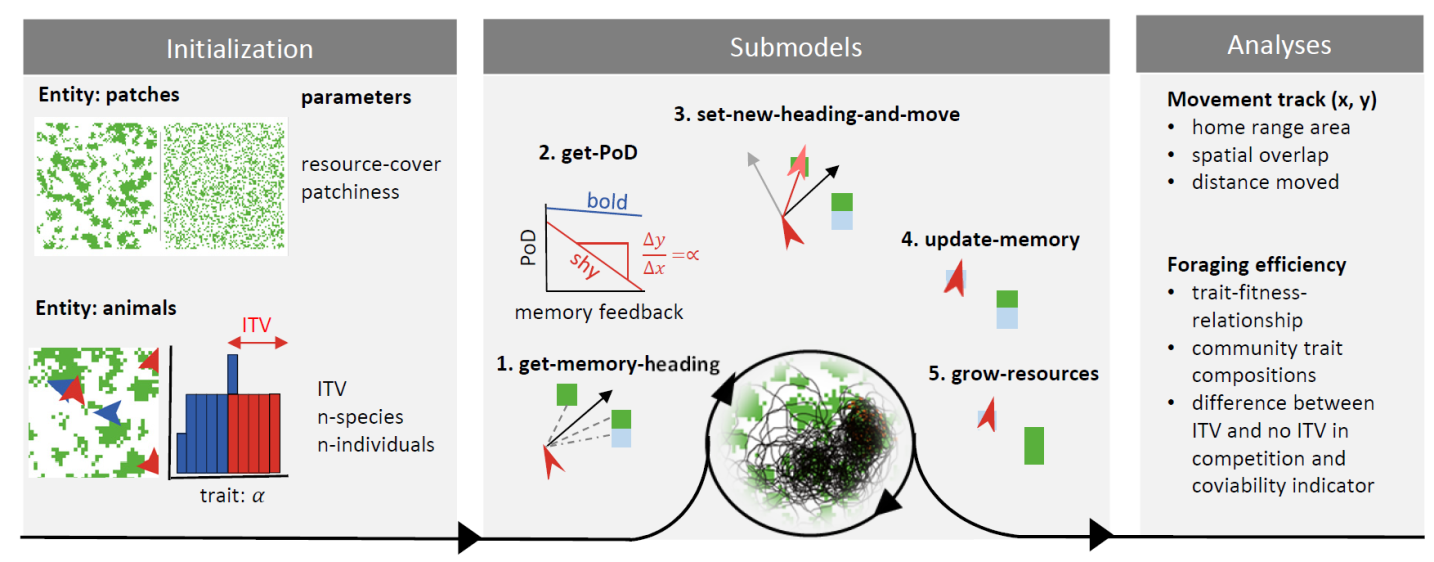

In software like ABM models, modularity also has application at a higher level, in the form of submodels. Creating models as assembles of submodels enables researchers to focus on their areas of interest and expertise without necessarily over reducing the complexity of everything else.

ABM has been, and still is, often critisised for being a too complex and arbitrary approach in its aim and domain. Truthfully, ABM models tend to overgrow in detail regarding certain aspects while bluntly simplifying other elements. This is primarily a combined effect of the internal limitations of the modellers and their teams (time, budget, expertise, etc.) and the lack of opportunities for code reuse. Modularity offers an exit to this.

Modules can be built as original contributions, implemented from published model specifications, reimplemented from another programming language, or taken and modified as code snippets. We will encounter all these cases later on in this tutorial.

There are many sources of potential modules. The most direct source is, of course, your relevant bibliography. Despite the number of models and modellers, the likely scenario is that the modules you need are still not available as usable implementations. In such cases, you might need to translate model specifications, with a varied level of formalisation, into a working piece of code. The less formalise is the original contribution, the harder will be the challenge. Thankfully, there are a few alternatives where modules can be taken almost without extra coding.

When using NetLogo, we first count with the Netlogo’s Models Library, a collection of implementation examples classified by discipline and domain. All files are included in the installation of NetLogo and can be accessed through File > Models Library. If you are interested in taking an evolutionary perspective, it is also worth checking the OpenEvo NetLogo Models. a collection of models made for learning by Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

The wide community of NetLogo users also hosts two extra libraries, the NetLogo User Community Models and the NetLogo Modelling Commons, where modellers from different disciplines can upload their models, and share and discuss them with others.

A similar initiative was created from modellers more strongly associated with the SES framework. Today named as CoMSES Model Library, former openABM, it holds almost the same amount of models as NetLogo Modelling Commons and, despite being cross-platform, the majority of entries are implemented in NetLogo. CoMSES also hosts a curated bibliographic database, which can help search subject-related models. Even though massive, it does not represent all ABM and related modelling being done worldwide. CoMSES relies on voluntary work, as most scientific associations do, and its updates rely on a relatively small community.

More recently, a growing group of researchers involved in ABM in archaeology, including myself, have created an initiative, Network for Agent-based modelling of Socio-ecological Systems in Archaeology (NASSA), whose principal goal is to create and maintain a public library of modules (i.e., formatted as modules). You are welcome to join our activities and help create this community asset (write me an e-mail!).

4.3.4 Being explorative

The last general recommendation to be made about doing ABM is: to be explorative. As mentioned, some have criticised ABM for being too speculative and arbitrary. Yes, ABM models often require many specifications to work, some of which escape the modeller’s expertise entirely. In front of this, we can either avoid ABM altogether or accept it, going the proverbial extra mile in making most “free decisions” based on a deeper study of possible design alternatives.

Similar to how we can use stochasticity, creating and exploring design alternatives is always a good idea to better understand our conceptual model’s weak points. Observing the differences in dynamics generated by those alternatives will help us decide how to define those uncertain areas further while reducing the risk of unconsciously running over important modelling decisions. In the tutorial, we will illustrate a few strategies for implementing and handling design alternatives.

4.3.5 Documentation

A short disclaimer before we start: the approach used here for conceptual modelling and model documentation is not considered a standard in the ABM community.

In the bibliography, you will find many other recommendations and examples, particularly those converging into the practices closer to Computer Science and Ecology. For example, many consider a necessary standard to be the Unified Modeling Language (UML), which includes many types of diagrams.

Derfel73; Pmerson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Use case diagram. Jvlivs, Copyrighted free use, via Wikimedia Commons

The Overview-Design-Details (ODD) protocol is also quite strongly advocated by ABM practitioners and constantly revisited and updated (Grimm et al. 2006, 2010, 2020; Müller et al. 2013).

After years of creating and reviewing ABM models, I would argue that these are not as useful or applicable as hoped, especially when the intended audience is greatly oblivious to simulation modelling and, of course, such standards. Consider that in other disciplines, a minimal knowledge of mathematical modelling, including simulation modelling, and programming is a common curricular requirement at the undergraduate level. For those of us pursuing this approach in archaeology and history, having ourselves an academic track in the Humanities, the time spent in learning documentation standards could be better used to improve one’s programming skills, for example. However, any student of ABM should be aware of these proposed standards and judge for themselves. Being informed about them, and effectively using them, will always get you into a better place as a modeller. I use simple text and generic graphs for this course, on the other hand emphasising the importance of maximum clarity in the code.

4.4 Learning resources

Textbook (Romanowska, Wren, and Crabtree 2021)