23 Case study and conceptual model

23.1 Evidence and case study

Having a generic conceptual model that covers the definition of a phenomenon and mechanism, we proceed to select a case study that offers both a real-world context and archaeological data to which we can adapt the Pond Trade model.

Paliou, Eleftheria, and Andrew Bevan. 2016. ‘Evolving Settlement Patterns, Spatial Interaction and the Socio-Political Organisation of Late Prepalatial South-Central Crete’. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 42 (June): 184–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2016.04.006.

Summary (by Google NotebookLM)

This research article investigates socio-political organization in south-central Crete during the late Prepalatial period (ca. 2300–1850 BC), a period before the well-documented Minoan palaces. Employing spatial interaction models and regression-based predictive modelling, the authors analyse settlement patterns and artefact distributions (specifically Minoan seals) to identify potential local power centres. The study addresses the challenges of incomplete archaeological data by incorporating simulated settlement locations, improving the accuracy of the analysis. The findings suggest the existence of three to four local power centres, rather than a single dominant centre, during the late Prepalatial period, with a shift towards a single dominant centre at Phaistos in the subsequent Protopalatial period. The study highlights the combined use of computational modelling and material culture evidence to understand past socio-political dynamics.

Takeaways for our conceptual model

- Case study: settlement interaction and the emergence of hierarchical settlement structures in Prepalatial south-central Crete

- Phenomena to represent: cycles of growth and collapse (i.e., fluctuations in the scale of site occupation). Focus on site interconnectivity and its relationship with settlement size.

- Main assumption: topography, transport technology, exchange network, settlement size, wealth, and cultural diversity are intertwined in a positive feedback loop (i.e. big gets bigger or busy gets busier).

- Dynamics we expect and want to explore: the long-term consolidation of central sites and larger territorial polities.

Since Paliou and Bevan (2016) also tackles research questions on settlement patterns and interactions, the study offers us an opportunity to compare ABM with other approaches, such as the gravity spatial interaction models referenced in the original study. Hopefully, you will gain an intuitive perception of the advantages and caveats of ABM in front of more analytical or data-driven approaches.

With site distributions and artefactual classifications, archaeology offers an opportunity for us to estimate aspects such as population density and economic and cultural interactions. However, to relate the socio-ecological past to the material evidence in the present, we must inevitably use an explanatory model. There are many published models relevant to this topic, several already mentioned by Paliou and Bevan (2016). However, few are formalised to some extent, and fewer are available as reusable implementations. Luckily, some of these are ABM models (see ABM in archaeology and References).

Our objective adapting the Pond Trade model to this case study is to delve deeper into the expectations of our current knowledge about the growth of settlements and the formation of local polities in this crucial period, preluding the Minoan palatial institution. As in the original paper, we will need to assume a series of conditions and behaviour rules, considered valid for this context, given historical and anthropological parallels. However, in an agent-based model, such assumptions can be made more explicit as part of the model and, thus, testable as an explanation.

As mentioned, ABM is particularly hungry for specifications, many of which are not even dreamed of by the average archaeologist. In this tutorial, we will try to maintain an intermediate level of model abstraction, avoiding many details that would normally be included in the ABM-SES approach in archaeology.

23.2 Extending the Pond Trade model

We advance with a minor revision to our previous conceptual model:

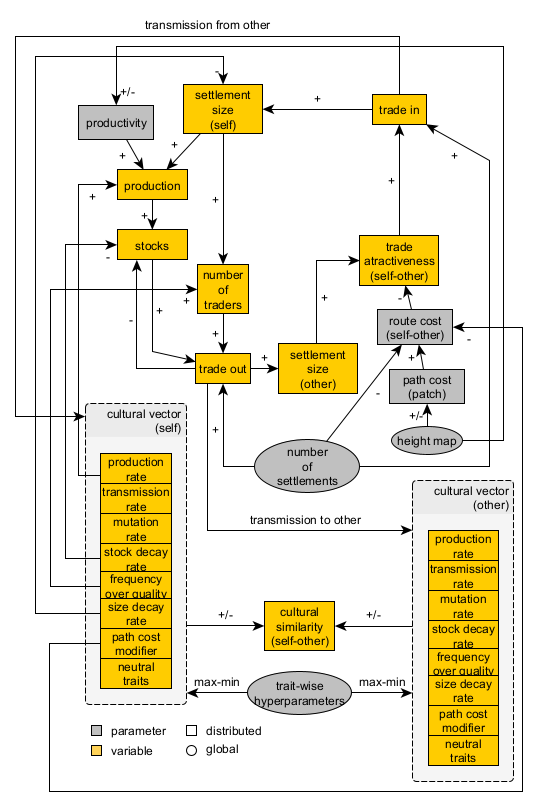

Pond Trade conceptual model at step 14 (second tier)

In addition to the core mechanism, we must consider another aspect to better approach our case study.

The Pond Trade model has several caveats. Like any other model, it is incomplete and greatly simplifies those aspects of reality that we chose not to prioritise. One of the most significant simplifications is that each settlement’s production is only dependent on a general term of productivity, independent of the land accessible to its inhabitants.

This limitation is not a significant problem if we are dealing with a straightforward terrain, like in the original Pond Trade where we only differentiate between land and water. However, we eventually aim to apply the model to a specific region and use the available geographical and archaeological data. Therefore, we lay out a potential expansion of the original Pond Trade, which will enable us to factor in the diversity regarding the land productivity around settlements.

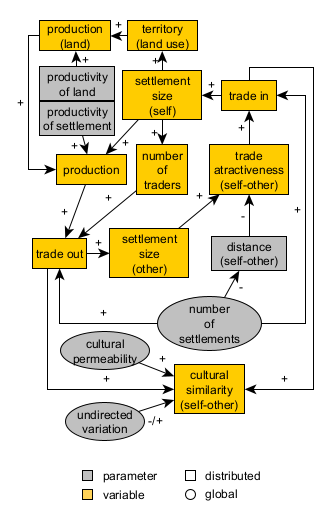

Mechanisms:

- ↑ settlement size → ↑ settlement territory

- ↑ settlement territory → ↑ production (of land)

- ↑ productivity (of land) → production (of land)

- ↑ production (of land) → ↑ production (of settlement)

Expanded Pond Trade conceptual model at start

Notice that, with this expansion, we are again introducing a positive feedback loop or splitting the one that already involves production. This time, however, instead of relying on a global parameter, we are regulating the process through a location-specific value (i.e., productivity of land).

Expected dynamics: production is ‘grounded’, i.e., dependent on each settlement catchment area size and productivity

23.3 Towards model implementation

To build the Messara Trade model, we will take several advanced steps. Through a sequence of module development, we will reach a final version that extends the Pond Trade model to a ‘grounded’ production process and contextual data that refers specifically to our case study.